Interviews

The “Aquaman” of Japan

Yosuke Furusawa

Breaking down the barrier separating reality and fantasy by manipulating the movement of fish

Interviewer/photographer: Kevin Zaleski, author: AltJapan Co., Ltd.

Furusawa isn’t a fisherman or a farmer, but you’d be forgiven for thinking otherwise as he emerges from one of his giant water tanks clad in chest-high rubber waders. He’s an engineer, and he has created something that evokes comparisons to that American comic-book superhero of old, Aquaman. Furusawa has invented a way to talk to fish. It doesn’t use words, of course, but rather carefully crafted underwater electrical fields to direct and corral schools of fish like a sheepdog herds its flock. This might not sound like much of a superpower, but the device’s potential impact on the world is in fact supersized.

Fish farming is big business – up to a $260 billion dollar business globally as of 2017. In 2016, the aquaculture industry produced between a hundred and seventy million tons and two hundred and two million tonnes of seafood. In fact, more fish are now farmed globally than caught in the wild. Yet ironically for a nation so intimately associated with seafood, Japan has long lagged behind the world when it comes to aquaculture. Part of this is due to a robust and politically powerful fishing lobby. The difficulty of farming certain prized species, such as tuna, as compared to catching them plays another role. As a result, just a quarter of the seafood consumed in Japan comes from the aquaculture industry. But times are changing. Climate change, environmental concerns, and a rapidly shrinking population mean there’s more of a need for aquaculture in Japan than ever, and Furusawa is forging new paths for underwater cultivation.

Despite a giant leap from his prior passions, Furusawa’s work still marvels in technological achievement.

From robots to fish

Furusawa’s background is in robotics, but a college internship in a laboratory that worked on artificial hearts instilled in him a deep fascination with the ways electronics can interact with living systems. He worked for a time at the company Cyberdyne, which makes exoskeletons: wearable machines that enhance human performance. In 2016 Furusawa launched Homura Heavy Industries in his hometown of Takizawa, Iwate Prefecture. It specializes in robots for use outdoors, with a focus on the aquaculture industry. In the office space, a half-dozen young researchers design components on multi-screen computers linked to an array of 3D printers, surrounded by shelves literally overflowing with technical manuals and science books.

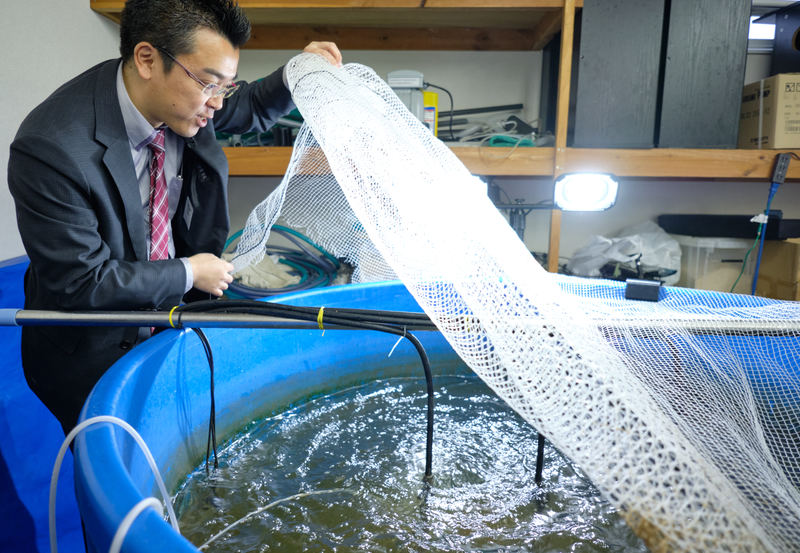

One of the company’s first commercial products was the “Marine Drone.” It’s an unmanned rowboat that can be programmed to dispense fish food over ponds or even target and disperse harmful wildlife, such as predatory birds, that threaten the stocks. But it is Furusawa’s ability to communicate with fish that he believes might prove the real game-changer. The “electric fish-cluster control” system, as he calls it, is located in an adjacent room housing tanks of water ranging from aquarium-sized to pond-sized. The largest holds ten tons of water and is more than large enough for a person to wade into, which Furusawa does when he needs to reposition a piece of equipment or make an adjustment.

The cluster control system involves placing electrodes along the walls of a tank. When activated, they generate an electrical field that fish can feel. The combination of electricity and water sounds like a recipe for injury, but Furusawa is quick to point out that this causes no harm to the fish. By stimulating their “bioelectric sense,” Furusawa can cause an entire school of fish to move at his command. He demonstrates the procedure in a series of specially constructed pools in his laboratory. “The biggest hurdle I face is in convincing people this is even possible,” he laments. It does sound like science fantasy, and even standing there in the same room, watching him use his electrodes to move a school of sardines from one side of a tank to another feels eerie, almost like a form of magic. It’s hard to believe your eyes. “It looks like a superpower,” he laughs. “But it’s electricity.”

Homura Heavy Industries’ ground floor is sprawled with tanks holding fish to conduct his superpower-like experiments.

Advantages

“Until now the main way of moving fish during the aquaculture process has been with nets,” he explains. “It’s labor-intensive and requires a high degree of skill. But my system lets you do the same thing with fewer people.” A tuna-farming operation, for example, requires some twenty to thirty people, a number of whom need to be trained SCUBA divers, for the fish are retrieved by hand at the end of the process. This isn’t simply automation in search of profits, however. It’s a response to a major demographic shift playing out in Japan right now: the rapid aging of the population. “When you go to the countryside, there are very few young people these days. So I wanted to automate to support the older folks doing the work.”

There’s another big advantage to using invisible electrical fields rather than physical nets. One of the biggest issues for fish-farmers is the inevitable abrasions and physical damage suffered by their stocks from contact with netting. Nobody wants stressed, injured fish, because they aren’t worth nearly as much from a product standpoint. Furusawa’s system, on the other hand, allows him to corral and move fish without any physical contact at all – a huge plus compared to traditional farming methods.

The world’s population is projected to hit nine billion by the middle of the 21st century, and our hunger for seafood only continues to grow. Yet the seas are literally running out of fish, with natural catches in decline year after year. How can we keep the world fed? Furusawa might not look the part of a fantastic underwater hero like Aquaman, but his similar “superpower” of being able to communicate with fish might just hold part of the answer. Aquaculture will play a key role in both feeding the world and in helping overfished seas recover, and any technology that facilitates its spread is a net gain – no pun intended.

“If the world could see [electric fish-cluster control] in action, fishing orthodoxy would change in an instant.”

Yosuke Furusawa

Born in Takizawa, Iwate in 1982. He received his MEng from University of Tsukuba in Japan in 2007. He has been involved in the launch of the production design and development of the welfare and medical Robot-suit HAL since he started working for the CYBERDYNE Inc, including the acquisition of ISO13482, ISO13485, IEC60601, & IEC62133 certifications. Currently, he is the founder of the Homura Heavy Industries Corporation.

Related URL:

https://www.hmrc.co.jp/